In a previous article, I addressed the question that I have heard from so many, “If Christianity is true and so well supported as you say it is, why do so many intelligent and apparently informed people not accept it?” Towards the close of that article I noted that many Christians feel intimidated when encountering a scholar with a PhD, a position at a major University, and a stellar publication record. Such, however, as I intend to show in this and a subsequent article, is not a guarantee of being a careful scholar.

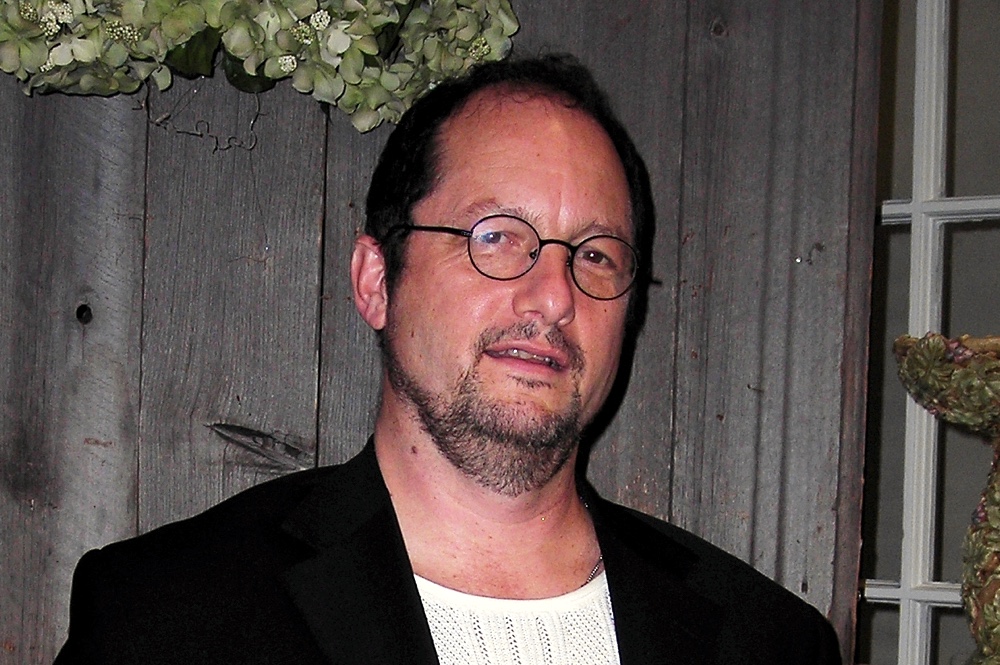

Dr. Bart Ehrman is the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He has written a number of books attempting to cast doubt on the reliability of the New Testament. I have made an extensive study of Bart’s work and have learned that when Bart Ehrman makes a claim, it is best to check the primary source for yourself, since if past experience is anything to go by, he is more likely to be misrepresenting his sources than otherwise. Even though Bart Ehrman has a PhD and a professorship position at a major University, he makes a lot of very elementary mistakes in his work. Let’s take as an example his book titled, Jesus Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible – And Why We Don’t Know About Them [1].

Space does not permit me to do justice to all of the the arguments presented in Ehrman’s book. So you are just going to have to trust me that I am not cherry picking examples that are unrepresentative of the book as a whole. In future articles, I will pick up additional errors from this and other books by Ehrman.

Our first example is from chapter 1 of the book. He writes on page 8,

Not only are there discrepancies among different books of the Bible, but there are also inconsistencies within some of the books, a problem that historical critics have long ascribed to the fact that Gospel writers used different sources for their accounts, and sometimes these sources, when spliced together, stood at odds with one another. It’s amazing how internal problems like these, if you’re not alerted to them, are so easily passed by when you read the Gospels, but how when someone points them out they seem so obvious. Students often ask me, “Why didn’t I see this before?” For example, in John’s Gospel, Jesus performs his first miracle in chapter 2, when he turns the water into wine (a favorite miracle story on college campuses), and we’re told that “this was the first sign that Jesus did” (John 2:11). Later in that chapter we’re told that Jesus did “many signs” in Jerusalem (John 2:23). And then, in chapter 4, he heals the son of a centurion, and the author says, “This was the second sign that Jesus did” (John 4:54). Huh? One sign, many signs, and then the second sign?

Now, let’s review the actual texts that Ehrman cites here.

- John 2:11 – “This, the first of his signs, Jesus did at Cana in Galilee.”

- John 2:23 – “Now when he was in Jerusalem at the Passover Feast, many believed in his name when they saw the signs that he was doing.”

- John 4:54 – “This was now the second sign that Jesus did when he had come from Judea to Galilee.”

Pay special attention to the text that I have highlighted in bold, since these are the sections of the texts Ehrman has omitted to tell you about. John 2:11 and 4:54 are talking about the first and second signs that Jesus did while in Galilee. The signs alluded to in John 2:23 were not in Galilee but in Jerusalem. Is Ehrman being dishonest, or is he merely incompetent? You decide.

Now let us take an example from chapter 2 of the book. This one pertains to the resurrection narratives (p. 48):

Who actually went to the tomb? Was it Mary alone (John 20:1)? Mary and another Mary (Matthew 28:1)? Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome (Mark 16:1)? Or women who had accompanied Jesus from Galilee to Jerusalem – possibly Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and “other women” (Luke 24:1; see 23:55)?

According to Bart Ehrman, John 20:1 indicates that it was Mary alone who went to the tomb. But is this actually what the text says? Apparently Bart Ehrman did not read as far as verse 2, in which we read,

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb. 2 So she ran and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.”

The use of the plural pronoun “we” in this text in fact presupposes that there had been other women who had been present with Mary at the tomb, so there is no contradiction here at all.

Bart Ehrman also claims in this chapter that Matthew has Jesus riding into Jerusalem seated upon two animals. He states on page 50,

In Matthew, Jesus’ disciples procure two animals for him, a donkey and a colt; they spread their garments over the two of them, and Jesus rode into town straddling them both (Matthew 21:7). It’s an odd image, but Matthew made Jesus fulfil the prophecy of Scripture quite literally.

But is this what Matthew says? Here is Matthew 21:7.

They brought the donkey and the colt and put on them their cloaks, and he sat on them.

What is the antecedent of “them”? The most plausible antecedent is the cloaks. Matthew is indicating that Jesus sat on the cloaks, not that he sat on both the donkey and the colt. In fact, since the colt never had been ridden, or even sat upon (as stated by Mark and Luke), its dependence upon its mother is very understandable (as implied by Matthew).

Chapter 2 of the book also has a selection of examples from Acts, which are just as appalling as his gospel examples. For example, according to Ehrman, Paul’s own words in Galatians contradicts the book of Acts. He writes on page 57,

According to Paul’s account, [the Jerusalem council] was only the second time he had been to Jerusalem (Galatians 1:18; 2:1). According to Acts, it was his third, prolonged trip there (Acts 9, 11, 15). Once again, it appears that the author of Acts has confused some of Paul’s itinerary – possibly intentionally, for his own purposes.

The problem is that Galatians does not say that at all. Paul writes in Galatians 1:18-19,

18 Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and remained with him fifteen days. 19 But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother.

That would be Paul’s first trip to Jerusalem following his conversion. In Galatians 2:1, Paul writes,

Then after fourteen years I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas, taking Titus along with me.

Where does the text say that this was only Paul’s second visit to Jerusalem? In fact, we learn from Acts 11 that between those two journeys Paul had gone to Jerusalem to bring aid to the saints affected by a famine. There would have been no purpose in Galatians for Paul to have mentioned this trip, as it did not relate to conferring with the apostles about the gospel he was preaching.

Ehrman also argues that there the gospels become progressively anti-Jewish and pro-Roman from Mark through to John. On page 44, Ehrman writes,

Finally, it is significant that in John’s Gospel, on three occasions Pilate expressly declares that Jesus is innocent, does not deserve to be punished, and ought to be released (18:38; 19:6; and by implication in 19:12). In Mark, Pilate never declares Jesus innocent. Why this heightened emphasis in John? Scholars have long noted that John is in many ways the most virulently anti-Jewish of our Gospels (see John 8:42-44, where Jesus declares that the Jews are not children of God but “children of the Devil”). In that context, why narrate the trial in such a way that the Roman governor repeatedly insists that Jesus is innocent? Ask yourself: If the Romans are not responsible for Jesus’ death, who is? The Jews. And so they are, for John. In 19:16 we are told that Pilate handed Jesus over to the Jewish chief priests so they could have him crucified.

Ehrman’s claim here is that, as we move from earlier to later gospels the gospels progressively shift the blame for Jesus’ death from the Romans to the Jews. Ehrman of course assumes the consensus position that Mark was written first, followed by Matthew, then Luke, then John. So let’s see to what extent each of the four gospels fits the pattern that Ehrman claims exists.

Mark, like all of the other gospels, describes the plot of the Jewish leaders and chief priests to kill Jesus. Mark, like all of the Synoptics, also records the plot of the chief priests and the bribe given to Judas to betray Jesus. Like all of the other gospels, Mark tells us that those who arrested Jesus in Gethsemane were sent from the chief priests, and that Jesus was tried by night before the high priest. He also tells us that the Jewish leaders delivered him to Pilate. And in Mark 15:9 and 14, Pilate tries to get the Jewish crowd to allow him to release Jesus. How does that fact square with Ehrman’s claim that, in Mark, Pilate and the Jewish leaders are agreeing on what has to be done?

How does Matthew fit this pattern? Ehrman points out that Matthew reports the Jews saying “His blood be on us and our children” (Matthew 27:25). This indeed is a very striking statement. But Matthew comes before Luke and John, and they report nothing of the sort. Thus, the contrast counts when Ehrman desires to show “development” from Mark to Matthew, but is conveniently passed over when Ehrman moves on to discuss Luke and John.

How does Luke fit this pattern? Luke omits the hand-washing scene found in Matthew 27:24-25. Luke 23:27 portrays a great crowd of people weeping and mourning as Jesus is led out to be crucified. This can hardly be considered to be more anti-Jewish than Matthew’s account.

How does John fit this pattern? Besides lacking the hand-washing scene in Matthew 27:24-25, John also omits mention of the Roman centurion who states “Truly this was the Son of God!” (Matthew 27:54; Mark 15:39) or “Certainly this man was innocent!” (Luke 23:47). But John, according to Ehrman’s paradigm, being the latest of the gospel authors, is supposed to be the most pro-Roman. Furthermore, in Mark’s gospel, Jesus is mocked by the Jewish leaders (Mark 15:29). But this mockery is not recorded in John. This is very surprising given the thesis that John’s gospel is further along the trajectory of anti-Jewish sentiment.

So, the next time a scholar who holds a PhD and a professorship position at a major University, like Bart Ehrman, attempts to challenge your confidence in the reliability of Scripture, do not be intimidated. Instead tell him that you would like to read his sources for yourself. Of course, you may at this point be wondering if I have been selective in cherry-picking a non-representative sample of Ehrman’s examples from his book. To assuage this concern, in part 2, I will review yet further examples of Ehrman’s objections to the gospels and reveal that this sort of sloppy scholarship represents not a deviation from the norm but rather a trend.

Footnotes

[1] Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them). (New York: HarperCollins, 2009).

21 thoughts on “Why You Should Not Be Intimidated by Bart Ehrman: A Review of Jesus, Interrupted (Part 1)”

This is been helpful

thank you

Thanks for this. Looking forward to the next one.

I think Bart’s objections are almost laughably petty. The gospel writers were writing at different times within the 1st Century and had their own worldviews and their own lenses through which they interpreted events. They may have interviewed different people who had different opinions or different memories. As to the angels-at-the-tomb thing and which women turned up – that’s just ridiculous. Imagine you asked Bart Ehrman to write down everything he remembered about his first day at college or university – who was at what party, where he was staying, what he had to eat, what was involved in the matriculation process, which buildings he had to register in etc. Then imagine you asked three other people Bart was with on his first day at university to report on the same things. They would all report different things. The memories would differ. People conflate and mix up memories. Indeed, if you had just invented a religion and wanted people to believe your leader was God and rose from the dead, you’d never have invented women discovering the empty tomb, because their testimony was considered unreliable.

worth reading…

Excellent work! Thank you, Jonathan.

Very insightful. Thank you.

Pingback: More Misrepresentations and Distortions by Bart Ehrman: A Review of Jesus, Interrupted (Part 2) - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

Sadly this shows that Bart Ehrman is looking for reasons to reject the gospel message. He doesn’t want it to be true and so ‘finds errors’. I understand where he is coming from. May the Lord open his eyes like he did to Saul and everyone who is a christian.

As opposed to every Evangelical I have ever met, who are so full of Cognitive Dissonance that they ignore all of the contradictions in the Bible.

Pingback: Finding Contradictions Where There Is None: A Review of Jesus, Interrupted (Part 3) - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

These are classic “errors” in the Bible, all of which have been thoroughly dealt with by many able scholars in years past. I remember reading some other writings seeking to destroy the Bible’s reliability and authority, and some of them seemed to be saying “The Bible wasn’t written the way I would have written it if I were writing a sacred book, so it can’t be right.” There seems to be little recognition of the conventions in writing of the era in which the documents were originally penned, and much grasping at trifling matters that are reconcilable if one is patient and thoughtful.

As someone above has said, if one does not want to believe (or be accountable to God), then plausible reasons can be found – whether or not they can stand up to close scrutiny is another matter, but reasons are available.

Thank you!!! Very helpful.

Pingback: Hard Evidence the Book of Acts Was Written by an Eyewitness? A Reply to Bart Ehrman - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

Pingback: A Reply to Bart Ehrman's Defense of Jesus, Interrupted on the MythVision Podcast - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

If you want to hear Bart defend himself regarding this article (and the other two), he did an interview on the MythVision YouTube channel about contradictions in the New Testament.

In my opinion he absolutely destroys Jonathan’s points above.

Did you even bother to read my detailed refutation of Ehrman’s “responses”?

https://jonathanmclatchie.com/a-reply-to-bart-ehrmans-defense-of-jesus-interrupted-on-the-mythvision-podcast/

Is it not more likely that untrue claims were made in/for a far less scrupulous society?

Pingback: A Reply to Bart Ehrman’s Defense of Jesus, Interrupted on the MythVision Podcast - answeringallah.com

Bart was once a Christian whose “intellect” lead him away from Christ. Have you ever considered praying for him?

Pingback: Contradictions in the New Testament - Professor Bart D. Ehrman - Corruption Buzz

Comments are closed.