When asked for what I consider to be the most compelling argument for the truth of Christianity, I often offer the cumulative force of the argument from prototypic foreshadowings of Christ and the new covenant which are so delicately interwoven into the Old Testament fabric. Just as one needs the Box Top to make sense of a jigsaw puzzle, so one needs Christ in order to properly understand what’s going on in the Old Testament. In this article, I present one of those foreshadows.

First, some background. Abraham, the progenitor of the Hebrew race, is said in Genesis to have had two sons. The sons were distinct in a number of ways. For example, they had different mothers. One son, Ishmael, was born of a slave woman (Hagar), whereas the other, Isaac, was born of a free woman (Sarah). Hagar was the Egyptian slave of Sarah, Abraham’s wife. Many years after God first promised a son to Abraham, Sarah had not yet borne him a son. Not wanting Eliezer of Damascus to be his only heir, he cried out to God in request for a son to be his heir, a request that resulted in God’s re-affirmation that “This man will not be your heir, but a son who is your own flesh and blood will be your heir.”

The years went by, and Abraham had still not conceived a son by his wife, Sarah. Sarah thus decided it was time to take matters into their own hands, and induced Abraham to father a child through her female slave, Hagar. Hagar thus conceived and gave birth to Ishmael. Abraham’s second son — the one that had been promised by God — was later conceived through his wife, Sarah.

The Apostle Paul explicated this event in his epistle to the church in Galatia. Our text is taken from Galatians 4:21-5:1:

Tell me, you who want to be under the law, are you not aware of what the law says? For it is written that Abraham had two sons, one by the slave woman and the other by the free woman. His son by the slave woman was born according to the flesh, but his son by the free woman was born as the result of a divine promise. These things are being taken figuratively: The women represent two covenants. One covenant is from Mount Sinai and bears children who are to be slaves: This is Hagar. Now Hagar stands for Mount Sinai in Arabia and corresponds to the present city of Jerusalem, because she is in slavery with her children. 26 But the Jerusalem that is above is free, and she is our mother.

In what sense was Ishmael (the child born through Hagar) born in the ordinary way? The answer lies not so much in the physicality of the conception, but rather in the fact that he was conceived through human scheming and planning — the way of the flesh: the way of works and self-effort. In contrast, Isaac was born by the free woman, Sarah. His conception was supernatural because the Holy Spirit had miraculously enabled Abraham and Sarah to conceive a child after she was far beyond the age of childbearing. When Isaac was born, his father was 100 and his mother 90 (Genesis 17:27; 21:5).

The conception of Ishmael may be considered analogous to the way of religious self-effort and works-based righteousness. The second is analogous to the way of trust in the promises of God, and God’s imputed righteousness. While Ishmael typifies those who have been born naturally (that is, those who place their trust in their own works and merits), Isaac typifies those who have had been born of the spirit through trusting in the promises of God and in the completed work of the Lord Jesus.

Paul then tells us that the two women (Sarah and Hagar) represent two covenants. Hagar represents the covenant of law and works, while Sarah represents the covenant of grace and faith.

The Old Covenant of law was given at Mount Sinai to Moses. Because the terms of the covenant were not possible for humanity to keep, it produced a type of religious slaves, bound to the master of the law from whom they could never escape. The descendants of Hagar (through Ishmael) eventually moved into the desert areas to the east and south of the Promised Land, and eventually came to be known as the Arabs and their territory as Arabia. It is highly significant that Mount Sinai is located on what is known today as the Arabian Peninsula. It was, in fact, between the sons of Sarah and Hagar that the modern Arab-Israeli animosity began, producing a perpetual conflict and tension between the two groups of people who trace their ancestry back to Abraham.

Paul notes that Hagar and Mount Sinai correspond to the present city of Jerusalem. He speaks of the first Jerusalem as present, showing he has in mind the earthly, historical city by that name. In the same way God chose Mount Sinai to be the geographical location in which he would deliver the Old Covenant to Moses, so he also chose Jerusalem as the geographical location in which to the Old Covenant would be propagated and exemplified. In this type, both locations are intended to represent the Old Covenant of law and works and the bondage and slavery that they produce.

The city of Jerusalem is also the city in which the New Covenant is established in the death and resurrection of Christ. But the New Covenant of grace was rejected by the Jews, and so — much like Mount Sinai in Arabia — Hagar still figuratively dwells in slavery with her children. In Paul’s day, most of Jerusalem’s inhabitants were in deep bondage and slavery to damning legalism, ritual, ceremony and self-effort.

Conversely, the spiritual descendants of Sarah (through Isaac) live in the Jerusalem above and are free, because she is our mother. The inhabitants of this heavenly Jerusalem are free from the slavery that comes from legalism and works-based self-righteousness. As Jesus said in John 8:36, “If therefore the Son shall make you free, you shall be free indeed.”

Paul continues, by quoting from Isaiah 54:

Be glad, barren woman, you who never bore a child; shout for joy and cry aloud, you who were never in labor; because more are the children of the desolate woman than of her who has a husband.

Originally, these words were penned by the prophet Isaiah, to cheer up the Jewish exiles in Babylon. In our present context, they are applied to Sarah, the barren woman whose barrenness seemingly stood as a barrier to the fulfillment of God’s promise. As freedom came once again to the nation in Babylonian captivity, so it would come to the people in captivity to the law and its death penalty.

Paul also discusses the result of being a spiritual descendant of Isaac. Just as in that time, when there was resentment of Isaac by Ishmael, those who are spiritual descendants of Isaac are still persecuted by the spiritual descendants of Ishmael. Indeed, when Abraham held a feast to celebrate Isaac’s weaning, Ishmael mocked the occasion. And so it is now also. Those who hold to salvation by works hate those who proclaim salvation by grace alone without works.

Paul concludes by noting that just as the Scripture says “Get rid of the slave woman and her son, for the slave woman’s son will never share in the inheritance with the free woman’s son,” so the persecutors and slaves of the law will be thrown out of Abraham’s spiritual household.

Paul concludes by remarking that “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery.” In other words, Paul is asking, “Why on earth would anyone want to go back to being a slave like Ishmael, in view of the freedom made available in Christ?”

The question thus arises, is all this tightly interwoven symbolism explicable as the result of happy happenstance? Or is it too much to be attributed to blind coincidence? I don’t think these deep theological meanings are being imposed on the text, nor do I think the text is stretched or strained by Paul’s analysis. It is also significant that, while Isaac was the ancestor of Jesus Christ himself (who opened the way of salvation through grace, thus freeing us from obligation to the law), Ishmael was the ancestor of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Muhammad was of Arabian descent, and the Islamic religion is based around Arabia (where Mount Sinai is to be found), and based on a legalistic system of salvation through one’s meritorious deeds and works, and keeping the Law.

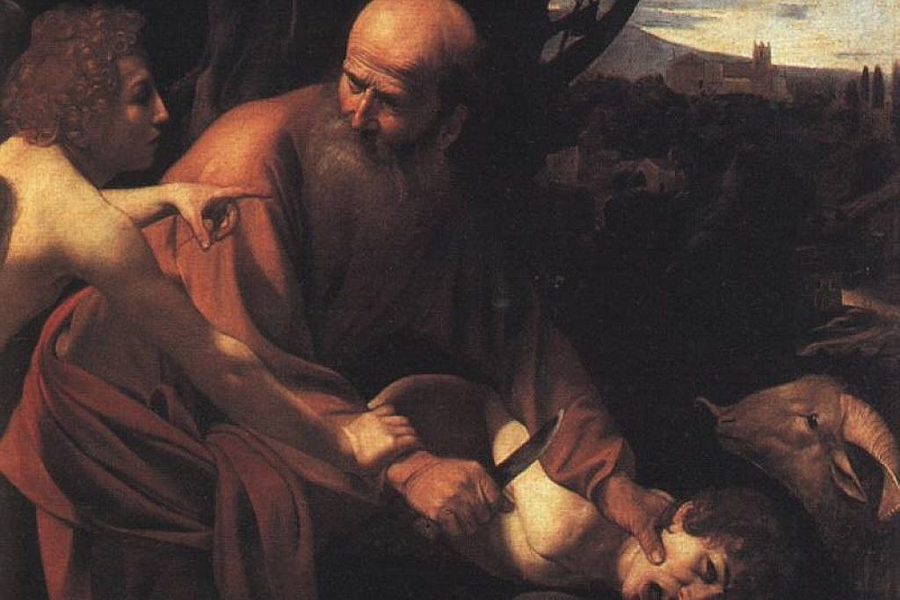

Note also that Isaac is the one ultimately laid on the alter in Genesis 22, and spared by the slaughter of a substitute, in the form of a ram caught by its horns in the bush. Note that the supplication of the Ram implicates that the ultimate Lamb of God (as had been promised on the way up Mount Moriah: “God will provide Himself the Lamb for the burnt offering”) was still to be provided, hence Abraham names the mountain “The Lord Will Provide”, saying “On the Mountain of the Lord, It Shall Be Provided” (note the future tense). Isaac carried the wood for his own sacrifice up the mountain, in a fashion similar to the manner in which Jesus carried his own cross for his ultimate sacrifice for sins. And The mountain on which these events unfolded is also thought to be the mountain on which our Lord was crucified.

When one considers this foreshadow of the gospel, in conjunction with the other mass of cumulative evidence from multi-disciplinary sources, I think one has very strong reason to think that the Christian worldview does indeed add up. Such intricate weaving of gospel threads throughout the fabric of the Old Testament is something which only God could do.

2 thoughts on “You Need the Box Top to Make Sense of the Jigsaw of the Old Testament: The Abraham Affair”

Pingback: Jesus Foreshadowed by Joshua the High Priest - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

Pingback: Christ in the Story of Ruth - Jonathan McLatchie | Writer, Speaker, Scholar

Comments are closed.