As many readers will know, I am a card-carrying Bayesian when it comes to hypothesis testing. I recently interviewed Tim McGrew (professor of philosophy at Western Michigan University) for the ID the Future podcast on the application of Bayesian reasoning to intelligent design. I have also previously been interviewed by Andrew McDiarmid on the same subject. In addition, I wrote a previous article, giving an introduction to Bayesian hypothesis testing in the context of intelligent design.

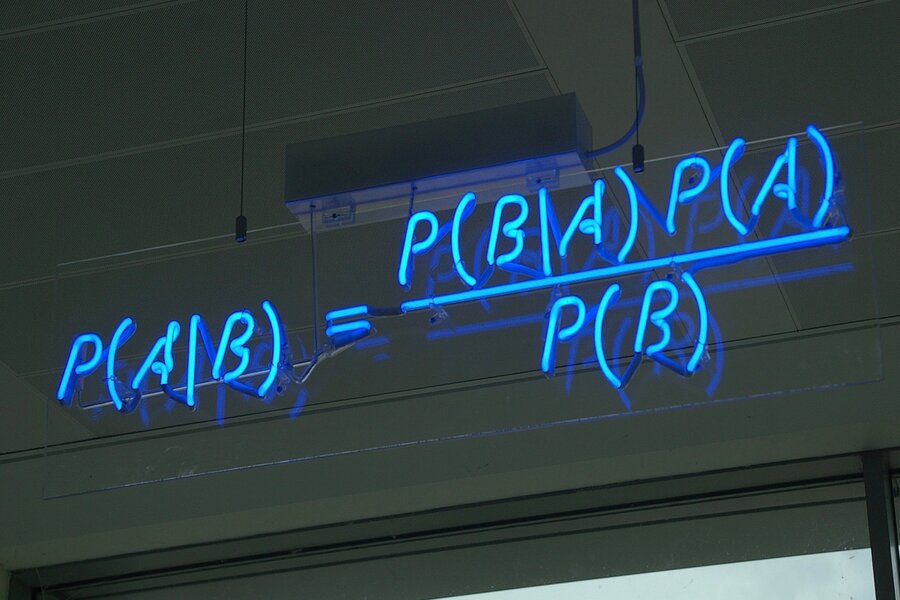

What Is Bayes’s Theorem?

In brief, Bayes’s theorem is a mathematical tool for modeling our evaluation of evidences to appropriately apportion the confidence in our conclusions to the strength of the evidence. A Bayesian understands the strength of the evidence for a proposition to be best measured in terms of the ratio of two probabilities, P(E|H) and P(E|~H) — that is, the probability of the evidence (E) given that the hypothesis (H) is true, and the probability of E given that H is false. That ratio may be top heavy (in which case E favors H), bottom heavy (in which case E disfavors H), or neither (in which case E favors neither hypothesis, and we would not call it evidence for or against H).

The Problem of the Priors

A common question I get asked when framing the argument in this way has to do with the prior probability — that is, the intrinsic plausibility of the hypothesis being true before the evidence is considered. Any inference based on Bayes’s theorem has to take into account the probability of the hypothesis being true based on the background information. For example, if we suppose that a cumulative Bayes factor is as high as a million (meaning, the observed evidence is a million times more likely to exist on the hypothesis being true than given that the hypothesis is false), this might sound impressive — but if the prior probability is only 1 in a billion, this yields posterior odds of the hypothesis being true of only 1 in 1,000, or 0.1 percent. Without information about the prior, the Bayes factor does not tell you much about the posterior odds.

Back Solving for the Prior

One approach to answering this challenge is to back solve for how low the prior probability needs to be in order to overcome the available evidence. For example, let us suppose (very conservatively) that there are only 20 clear-cut and independent examples of biological design. These could include unique protein structures, irreducibly complex biochemical systems, embryonic developmental pathways, and so forth. Moreover, let us make a further (extremely conservative) assumption that the average Bayes factor of these lines of evidence is 1,000 (given the astronomical rarity of even single protein folds, this is very generous). This would already yield a cumulative Bayes factor of 1060 (meaning, the evidence is 1060 times more likely to exist on design than on its falsehood). Even if our prior probability is as low as v, the posterior odds would still be as high as 0.99.

One can then argue that, even though it is difficult to put a precise value on the prior probability of intelligent design, it is surely much, much higher than 1 in 1058 — especially given our independent evidence of design in the physical sciences (such as the fine-tuning of the physical constants, or the prior environmental fitness of nature) and the fact that our universe appears to have a beginning (which is significantly less surprising on theism than on atheism). Moreover, those of us (such as myself) who think that there is strong independent evidence of the truth of revealed religion may also factor this consideration into our assessment of the prior probability of real biological design.

Of course, in reality the actual cumulative Bayes factor is much, much higher than 1060. But I hope this illustrates that it is difficult to reasonably maintain that the prior probability of actual design in biology is low enough to overcome the torrent of evidence in its favor.

This article was originally published on February 11, 2025, at Evolution News & Science Today.